A non-invasive spinal cord stimulation technique may pave way for much cheaper therapy for paralysis patients, a new study has shown.

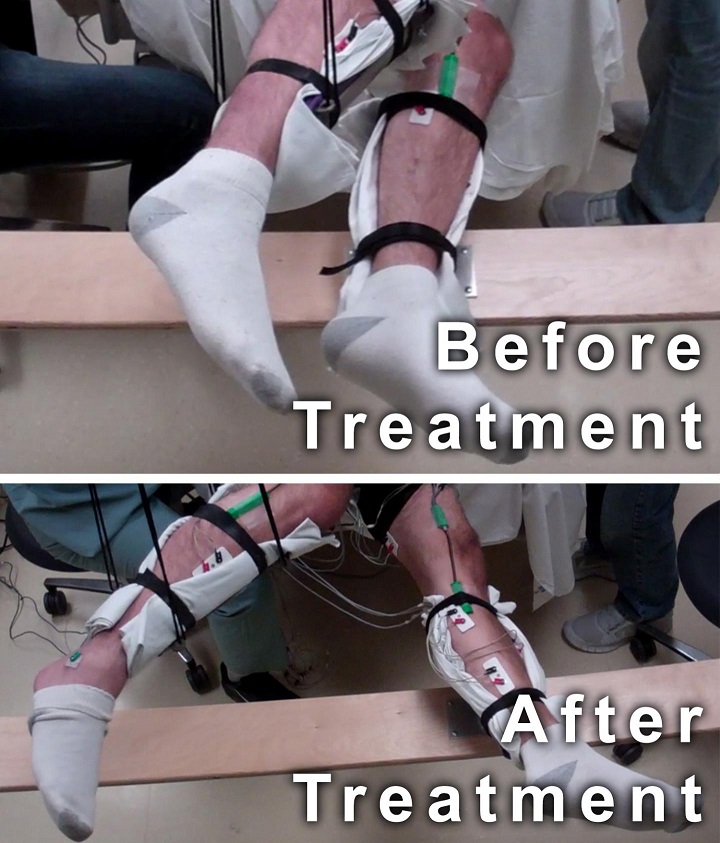

Five men with complete motor paralysis were were given one 45-minute training session per week for 18 weeks. During the session researchers placed electrodes at strategic points on the skin, at the lower back and near the tailbone and then administered a unique pattern of electrical currents. For four weeks, the men were also given twice daily doses of buspirone, a drug often used to treat anxiety disorders.

In addition to stimulation, the men received several minutes of conditioning each session, during which their legs were moved manually for them in a step-like pattern. The goal of the conditioning was to assess whether physical training combined with electrical stimulation could enhance efforts to move voluntarily.

While receiving the stimulation, the men were instructed at different points to either try to move their legs or to remain passive.

Patients were able to move their legs while suspended in braces that hung from the ceiling, allowing them to move freely without resistance from gravity. Though movement in this environment is not comparable to walking; the results signal significant progress towards the eventual goal of developing a therapy for a wide range of individuals with spinal cord injury.

The men in the study ranged in age from 19 to 56; their injuries were suffered during athletic activities or, in one case, in an auto accident. All have been completely paralyzed for at least two years. Their identities are not being released.

“These encouraging results provide continued evidence that spinal cord injury may no longer mean a life-long sentence of paralysis and support the need for more research,” said Dr. Roderic Pettigrew, director of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

CREDIT

Edgerton lab/UCLA

“These findings tell us we have to look at spinal cord injury in a new way,” said V. Reggie Edgerton, senior author of the research and a UCLA distinguished professor of integrative biology and physiology, neurobiology and neurosurgery.

At the initiation of the study, the men’s legs only moved when the stimulation was strong enough to generate involuntary step-like movements. However, when the men attempted to move their legs further while receiving stimulation, their range of movement significantly increased.

After just four weeks of receiving stimulation and physical training, the men were able to double their range of motion when voluntarily moving their legs while receiving stimulation. The researchers suggest that this change was due to the ability of electrical stimulation to reawaken dormant connections that may exist between the brain and the spinal cord of patients with complete motor paralysis.

Surprisingly, by the end of the study, and following the addition of buspirone, the men were able to move their legs with no stimulation at all and their range of movement was–on average–the same as when they were moving while receiving stimulation.

“It’s as if we’ve reawakened some networks so that once the individuals learned how to use those networks, they become less dependent and even independent of the stimulation,” said Edgerton.

Edgerton and his research team also plan to study people who have severe, but not complete, paralysis. “They’re likely to improve even more,” he said.