One of the most common ear problems in children otitis media with effusion (OME) also known as ‘glue ear’ can be treated with a simple procedure involving a nasal balloon, researchers have revealed.

As many as 200,000 children in the UK alone visit their GPs with complaints about hearing problems due to ‘glue ear’ and according to researchers doctors can avoid the unnecessary and ineffective use of antibiotics in this case and instead guide their patients to opt for the simple nasal balloon procedure to reduce the impact of hearing loss.

OME is very common for young children to develop and in this condition the middle ear fills with thick fluid that can affect hearing development. There are frequently no symptoms, and parents often seek medical help only when hearing difficulties occur.

In most cases doctors prescribe treatments for ‘glue ear’ that involve antibiotics, antihistamines, decongestants and intranasal steroids, but according to Dr. Ian Williamson, Primary Care and Population Sciences, University of Southampton, UK, all these are not only ineffective, but also could have unwanted side effects.

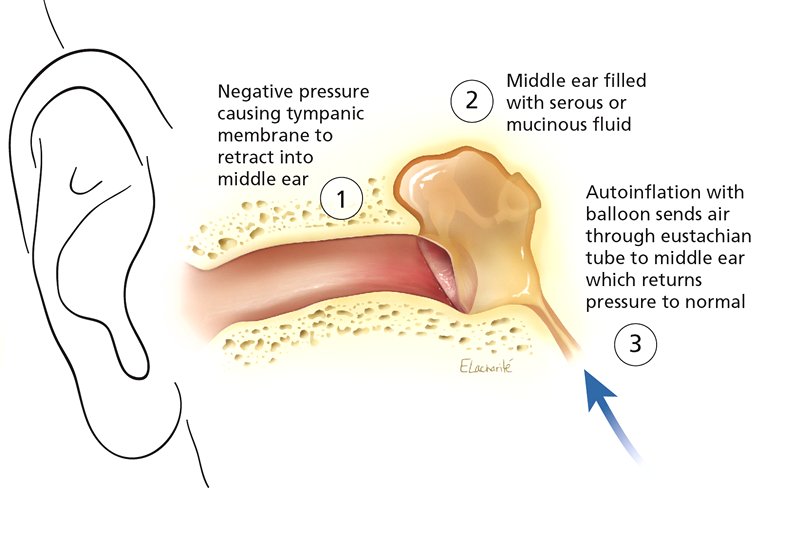

Nasal balloon autoinflation is a technique of ventilating the middle ear by the Eustachian tube using a purpose manufactured balloon. Inflating the balloon via the nose increases the pressure in the nasopharynx and opens the Eustachian tubes equalising the middle ear pressures thereby promoting drainage of middle ear effusions.

In the randomised controlled trial, researchers in the UK, checked out the possibility of using autoinflation with a nasal balloon on a large scale to benefit children in primary care settings. 320 children aged 4 to 11 years from family practices in the UK who had recent histories of otitis media and effusion with confirmed fluid in one or both ears were selected for the controlled trial.

The children were randomly assigned to either a control group that received standard care or a group that received standard care with autoinflation three times a day for 1 to 3 months. The children receiving autoinflation were more likely than those in the control group to have normal middle-ear pressure at both 1 month (47.3 per cent and 35.6 per cent, respectively) and 3 months (49.6 per cent and 38.3 per cent, respectively) and have fewer days with symptoms.

“Autoinflation is a simple, low-cost procedure that can be taught to young children in a primary care setting with a reasonable expectation of compliance,” write the authors.

Authors of the study add that the use of autoinflation technique in young, school-aged children with otitis media with effusion is not only feasible and effective, but is safe as well. The technique clears effusions and improves important ear symptoms, concerns and related quality of life over a 3-month watch-and-wait period.

They suggest that this treatment should be used more widely in children over age 4 to manage otitis media with effusion and help treat the associated hearing loss.

In a related commentary, Drs. Chris Del Mar and Tammy Hoffman, Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Bond University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, write “At last, there is something effective to offer children with glue ear other than surgery.” Surgery to insert drainage tubes can help a select minority of children.

“Autoinflation is one of a number of effective nondrug interventions typically underrepresented in research and clinical practice,” state the authors.

The authors note that there are barriers to using nondrug therapies widely in clinical practice. In the case of autoinflation, doctors need to know about the technique’s effectiveness, and how it is done, and must be able to instruct patients and families in how to use it.

The study has been published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).